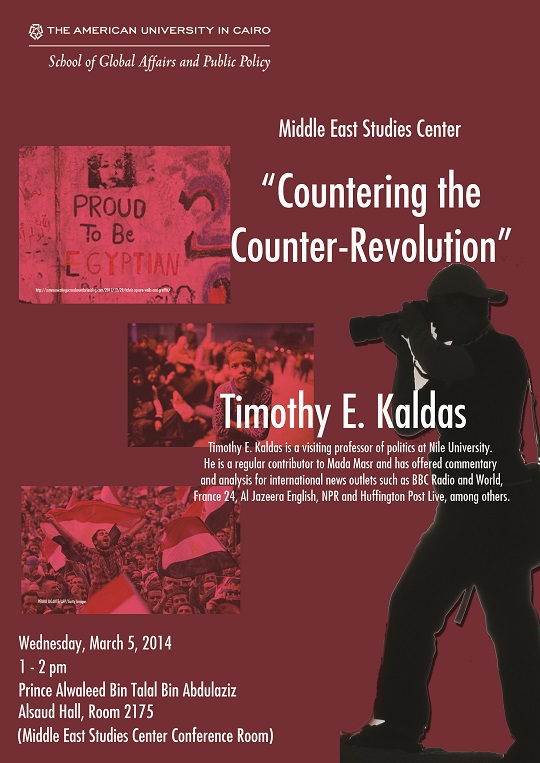

On 5 March 2014, the Middle East Studies Center at the American University in Cairo hosted political scientist Timothy Kaldas for a lecture titled “Countering the Counter-Revolution.” Kaldas is a professor at Egypt’s Nile University whose work can be found on Mada Masr and other media outlets.

Following the ouster of President Mohamed Morsi in July, and the subsequent return of the Egyptian military to the political spotlight, activists in Egypt have struggled with how to proceed on the revolutionary path. For Kaldas, the first step in that process is admitting mistake. In his talk, Kaldas identified a number of key mistakes that Egypt’s political opposition has made over the past three years. At the heart of these mistakes, Kaldas suggested, was short-sighted and opportunistic collaboration with elements of the old regime. Not only did the post-Mubarak opposition underestimate the military’s willingness to relinquish political power and “return to the barracks,” they also failed to properly define “the regime” they were fighting against. In light of the recent cabinet re-shuffle, which designated Ibrahim Mehlib, a former senior member of Hosni Mubarak’s National Democratic Party (NDP), to the premiership, Kaldas argued that “the regime” is far from toppled.

Noting the explosion of pundits offering commentary on Egyptian current events, Kaldas took care to avoid rigid prescriptions or predictions for Egypt’s future. Rather, he encouraged an honest discussion on how to move forward in these difficult times. Kaldas emphasized the need to engage with people on a more effective level, building the kinds of connections and networks that translate into real political momentum. While Kaldas concurred that “democracy is more than elections,” he also argued: “elections are an important part of democracy.” Indeed, in a country of over eighty million, Kaldas sees elections as a crucial mechanism for arbitrating political disputes. The recent constitutional referendum aside, Kaldas expressed optimism for a competitive electoral process in Egypt. Kaldas pointed to the 2012 presidential elections as evidence that “Egyptian voters are free agents,” with room for convincing and debate. He noted that in the 2012 election, whose final round pitted former regime player Ahmed Shafiq against the Islamist candidate Mohamed Morsi, six out of ten voters voted for non-Islamist candidates in the first round.

However, in order to establish a free and fair electoral process, Kaldas indicated a number of measures that Egypt’s rapidly evolving governments must take. He criticized Egypt’s single-member district voting system, which essentially restricts elections to only two or three competitive parties. This model, which has historically benefitted the NDP and Islamist political parties, hinders the establishment of new, post-revolution parties, Kaldas argued. He also highlighted weaknesses in the new constitution, which offers few mechanisms in terms of balancing power between the governments’ branches. Lawmakers must instead work under the assumption that a “good leader” is impossible, and enact according measures to prevent over-extensions of power. Putting these two ideas together, Kaldas suggested: “we need a more cynical attitude towards political leadership, and a less cynical one towards voting and the people.”

As Kaldas opened his discussion to the audience, he acknowledged that focusing on elections and lawmaking may speak, paradoxically, more to the success of the counter-revolution rather than the reversal of it. However, Kaldas stressed that although “talking about electoral systems is not very revolutionary,” activists must pair the “negative tactics” that oust governments with the political ones that build them. In the absence of political programs, Kaldas argued, successive governments will continue to manipulate the intense pressure on the Egyptian street, diffusing it until it fizzles out.

“We need a more cynical attitude towards political leadership, and a less cynical one towards voting and the people.”

-Timothy Kaldas

![[Logo of the American University in Cairo Middle East Studies Center. Image from aucegypt.edu]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/mescauc.jpg)